It is just after dusk in New Orleans on an evening early in May after World War II. In front of a shabby apartment building on a street named Elysian Fields, a white and a black woman are sitting on the steps while piano music plays in a nearby tavern. The white woman, Eunice, lives in the building’s upstairs apartment. The black woman lives nearby. Two white men in work clothes–Stanley Kowalski and his friend Mitch, both no more than 30–round the corner.

Stanley and his wife, Stella, about 25, occupy the first-floor apartment. After Stanley shouts for her, she steps out on the landing and he throws her a package of meat. He and Mitch then reverse direction to go bowling at an alley around the corner. Stella decides to follow and watch them.

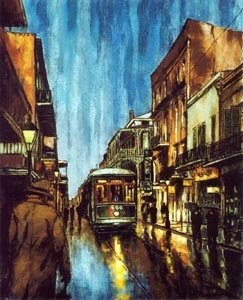

A moment later, Stella’s sister, Blanche DuBois, rounds the corner with a valise after arriving from Laurel, Mississippi. She checks an address on a slip of paper, then looks in disbelief at the apartment building. Could Stella really live in such a run-down dwelling? Blanche, about 30, is elegantly attractive but somewhat fragile and vulnerable. In her white suit, complemented by pearl earrings and white gloves, she is out of place in this working-class neighborhood. When Eunice asks whether she is lost, Blanche says, “They told me to take a street-car named Desire, and then transfer to one called Cemeteries and ride six blocks and get off at–Elysian Fields.” Eunice confirms that Blanche has come to the right street and right address, 632. The black woman goes to the bowling alley to fetch Stella.

After the sisters reunite and exchange pleasantries, Blanche looks for liquor and finds it, and Stella does the pouring because Blanche is shaking. Blanche assures her sister that she is not a drunkard but “just all shaken up and hot and tired and dirty.”

Blanche says she is on leave from her job teaching English at a high school in Laurel. In fact, she was fired for promiscuous behavior with a teenager. Pretentiously aristocratic, Blanche bemoans her sister’s plebeian surroundings. The apartment is run-down and spare, with only a kitchen and a bedroom–separated by a curtain–and a small bathroom. Blanche fishes for compliments about her appearance, asks for another drink, and wonders whether it will be proper for her to stay in such close quarters with Stella’s husband roaming about. Stella tells her that everything will be fine, although she cautions Blanche that Stanley’s friends are common and unrefined. Blanche then informs Stella that creditors back in Laurel have seized their family homestead, Belle Reve, even though Blanche “fought for it, bled for it, almost died for it.” She scolds Stella for not staying behind in Mississippi to help manage the property.

“You just came home in time for funerals, Stella,” she says.

The upshot is that Stella will never inherit a single cent from her share in the property, because there is no property. After Stanley arrives home and hears the news, he demands evidence of the property loss. He is crude and mouthy, not at all afraid to speak his mind, and suspicious. Blanche allows him to see the appropriate legal documents, which she has brought with her, that confirm the loss. Stanley says he will have a lawyer examine the papers, adding, “You see . . . a man has to take an interest in his wife’s affairs–especially now that she’s going to have a baby.” It is the first time Stella has heard of her sister’s pregnancy, and she congratulates Stella.

Stanley’s friends–Mitch, Steve, and Pablo–arrive for a poker game on the kitchen table. Hours later, at 2:30 in the morning, while the boys are still playing cards, Stella introduces Blanche to Mitch–Harold Mitchell–who works in the spare-parts department at the plant employing Stanley. Blanche seems interested in Mitch. Unmarried, he lives with and watches over his ailing mother. After he asks Stanley to deal him out, he talks with Blanche. She tells him that she’s younger than Stella (although she’s five years older) and that she is in New Orleans to look after Stella–“She hasn’t been well, lately”–even though she is there because she has nowhere else to go. She also says she is an old maid schoolteacher (although she was married once to a homosexual who committed suicide), and that she teaches high school English (although she was forced out of her job for having an affair with a student).

When Blanche plays a radio and dances suggestively, Mitch imitates her movements. Irritated by the noise, Stanley–now full of drink–throws the radio out the window. Stella scolds him and Stanley moves menacingly toward her. She runs. He follows and strikes her. After the other men restrain Stanley, Mitch says, “Poker should not be played in a house with women.” Stella goes upstairs with Blanche to Eunice’s.

After the card game, Stanley enters the hallway and calls upstairs repeatedly for “my baby.” Eventually, Stella comes down and they embrace tenderly on the steps, and Stanley carries her to bed. When Blanche later comes downstairs, she glances in at Stanley and Stella in carnal passion and runs outside. Mitch materializes from around the corner, and he and Blanche have a cigarette, sit down, and talk. Romance blossoms.

The next day, while Stanley is out getting the car greased, Blanche tells Stella that she’s married to a “madman” and urges her to abandon Stanley. Stella, however, shrugs off Stanley’s violent behavior of the night before and assures Blanche that he is really gentle and loving. Blanche says she “trembles” for Stella. A train rumbles by while the sisters continue their conversation in the bedroom. Stanley returns, unheard and unseen by the sisters, and overhears Blanche criticizing him: “He acts like an animal, has an animal’s habits. Eats like one, moves like one, talks like one!”

Over the next several months, Stanley and Blanche become mortal enemies, and Stanley dedicates himself to her destruction while she keeps company with Mitch. Opening up to Mitch, she tells him about her deceased husband, Allen Grey, who killed himself after she found out he was a homosexual and told him he disgusted her while they were out dancing a polka called the Varsouviana. Meanwhile, Stanley probes Blanche’s past and gets “the dope” on her from a supply man at his plant who regularly travels through Laurel and stays at the Flamingo Hotel there. He has told Stanley that Blanche carried on affairs with many men while living at the Flamingo, a second-rate hotel, and was evicted because of her promiscuous behavior.

“Did you know,” he says to Stella, “that there was an army camp near Laurel and your sister’s was one of the places called ‘Out-of-Bounds’?”

While Stanley is laying out the dirty details, Blanche is bathing in the bathroom, singing the lyrics of "Paper Moon": "It's only a paper moon, Just as phony as it can be– / But it wouldn't be make-believe If you believe in me."

Stanley also tells Stella that Blanche is not on a “leave of absence” from her teaching job but was “kicked out” of the high school before the end of the spring semester as the result of an affair with a 17-year-old. Stella says she doesn’t believe the stories but admits that Blanche did “cause sorrow” at home and was always “flighty.” While defending her sister, Stella says Blanche suffered a devastating blow when she was young and married to a young man (Allen Grey) who wrote poetry. She worshipped him but found out he was a “degenerate.”

While talking, Stella pokes candles into a cake, saying it is Blanche's birthday and Mitch has been invited. However, Stanley says Mitch won’t be attending. It seems Stanley has tattled on Blanche to Mitch and, Stanley says, Mitch has “wised up.”

“He’s not going to jump in a tank with a school of sharks,” Stanley says.

Later, Stanley gives Blanche a birthday gift: a bus ticket back to Laurel. His behavior upsets Blanche. Suddenly ill, she retreats to the bathroom. While Stella rebukes Stanley for his cruelty, she goes into labor pains, and Stanley takes her to a hospital.

Hours pass. Blanche drinks and packs her clothes. In the giddiness of her drunken state, she dresses in a white evening gown, a pair of silver slippers, and a rhinestone tiara. While she is in the bedroom admiring herself, Stanley returns after stopping at a bar for a few drinks and two quarts of beer. He tells Blanche that Stella is still in labor and that the baby will not come until morning. Stanley removes his shirt and opens a quart of beer, then enters the bedroom to remove pajamas from a bureau drawer. He asks Blanche why she is wearing “those fine feathers.” She fabricates a story, saying she has received a telegram from an old beau, Shep Huntleigh, inviting her on a Caribbean cruise. She says Huntleigh is a millionaire who lives in Dallas, “where gold spouts from the ground.”

“Well, it’s a red-letter night for us both,” Stanley says. “You having an oil-millionaire and me having a baby.”

After Stanley returns to the kitchen, Blanche tells him that Huntleigh respects her and that she, as an intelligent and cultivated woman, has much to offer him. Then she insults Stanley, saying, “I have been foolish–casting my pearls before swine. . . . I’m thinking not only of you but of your friend, Mr. Mitchell [who] came back [and] implored my forgiveness.” But, she says, she bid farewell to him.

Stanley asks, “Was this before or after the telegram came from the Texas oil millionaire?”

“What telegram?”

Her response gives her away. Stanley says was she lying not only about the Caribbean cruise but also about Mitch’s return visit because “I know where he is.” Then he says, “Take a look at yourself in that worn-out Mardi Gras outfit, rented for fifty cents from some rag-picker. And with that crazy crown on! What queen do you think you are?” He answers his own question, saying, “The queen of the Nile! Sitting on your throne and swilling down my liquor!”

Stanley reenters the bedroom and goes into the bathroom. Frightened, Blanche picks up the phone receiver and requests the number of “Shep Huntleigh of Dallas,” who she says is so well known that she need not provide the operator an address. Moments later, she cancels the call and asks for Western Union to send a message that she is in “desperate circumstances.” Stanley emerges from the bathroom in his pajamas. He leers at her. She smashes the top of a bottle and threatens him with the jagged edge. He subdues and rapes her.

Weeks later, Stella packs Blanche’s belongings while Stanley plays poker with Mitch, Steve, and Pablo. Eunice comes down and asks about Blanche, who is bathing. Blanche is now deeply disturbed–in fact, insane. Stella answers that she told Blanche arrangements were made for her to rest in the country. Stella also says, “I couldn’t believe her story [about the rape] and go on living with Stanley.”

When a doctor and a matron (nurse) arrive for Blanche, Blanche struggles against them. Stella says, “Oh, God, what have I done to my sister?” Stanley soothes Stella as the doctor and matron take custody of Blanche for treatment in an institution. The poker game continues as Steve says, “This game is seven-card stud.”

_05.jpg)